Scope

The Hymn Tune Index is defined as a comprehensive census of tunes associated with English-language hymns found in sources printed in or before the year 1820. In this section the key words of that definition will be explained in detail.

Hymns

A hymn is simply a religious lyric, and is probably as old as religion itself. The principal form of hymn recognized today in Western Christianity, however, is a metrical, strophic religious lyric in language of a simple and popular kind. It is generally rhymed as well, but that is not a necessary part of our definition. Historically, the hymn in this form originated with St. Ambrose in the fourth century.

A hymn, for our purposes, must be capable of being sung to a repeated tune. Hence it must be both metrical and strophic: built up of stanzas which have the same structure of lines, stresses, and syllables, although some irregularity in the number of syllables can be accommodated if it does not change the number of stresses in each line.

Some hymns have only one stanza. Strictly speaking, they cannot then be 'strophic'. Yet a text that has a clear metrical structure of one of the standard types, and is set to be sung to a tune that is also of a standard hymn-tune type, will not have been excluded because it has only one stanza. (A good example is Thomas Ken's metrical doxology, 'Praise God, from whom all blessings flow', found by itself in some modern hymnals.)

During the Reformation and after, a distinction was drawn between hymns and metrical psalms. A hymn was an original poem on a religious subject, while a metrical psalm was a verse translation of one of the 150 biblical psalms, or of a part of one of them, such as 'All people that on earth do dwell', William Kethe's version of Psalm 100. Between these categories fell metrical paraphrases of other parts of the bible, such as Tate and Brady's 'While shepherds watched their flocks by night', from Luke 2, 8-14; versifications of liturgical texts, such as 'All my belief and confidence', from the Apostles' Creed; and free paraphrases of the psalms, such as Isaac Watts's 'Jesus shall reign where'er the sun', from Psalm 72, 8-19. But in all cases the result was something structurally indistinguishable from a hymn, and subject to the same options for musical treatment. There is no metrical psalm tune that cannot also serve as a hymn tune, and there are few that have not actually done so.

The historical and theological importance of the psalm/hymn distinction is recognized. For example, it was a chief cause of controversy in Presbyterian churches in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. But it has no relevance to the task of indexing metrical psalm and hymn tunes. In this work, therefore, as in most modern hymnals, 'hymn' is used in a generic sense to cover all sacred lyrics in strophic metrical form.

There remains the question of what is 'religious'. A hymn text is sacred rather than secular. However, songs 'sacred' to Anacreon, Apollo, Bacchus, Phoebus, or Venus, common enough in eighteenth-century glees and catches, do not fall within our purview. Hymns of Jewish, Moslem, or other religions do not arise, since we know of none printed in English with tunes before 1820. This Index is thus wholly concerned with Christian hymns, both in the churches and outside them. But many hymn-like texts are only vaguely Christian in reference, while their prevailing character is unitarian, deist, humanist, masonic, ethical, philanthropic, patriotic, or sentimental. To exclude such texts by definite criteria would be not only dauntingly difficult, but also historically unjustified: many Christian communities intermixed such texts in their worship, especially during the last hundred years of our period.

Ther guiding principle is by the context in which we have found such hymns. A deist hymn in a clearly Anglican collection, for example, will have been ruled in, while the same text might have been ruled out in a separate sheet-music publication, or in a collection of glees or masonic songs. For songs published individually (as sheet music, in periodicals, or in collections of mainly secular music) we have tended to exclude borderline cases. (An exception is 'God save great George our king', later more often called 'God save the King'. Its first appearance was in an anthology of theatre songs and domestic music: see tune no. 1687.)

'Christian' practice, referred to above, is used in the widest of senses. It embraces all denominations, from Roman Catholics (insofar as they used hymns in English) to Quakers (insofar as they sang at all); and it includes hymns intended for use in home or school, and hymns with no specified intent.

English-language

This is an index of English hymn tunes, but with the word 'English' used only in its linguistic sense. It covers hymns and hymnals of any provenance, including many Scottish, Irish, and American ones, that are English only in their use of the language.

Before a tune is included, therefore, we must be satisfied that it was intended, in the particular source under consideration, to be sung to a hymn text in English. Sometimes an English text is printed with the tune, or identified by a reference. If it is not, we look to the title page, preface, or other contextual evidence to see whether the compiler intended the tune to be sung with an English-language hymn. Generally the answer to this question is not in doubt.

It does not matter, for the application of this principle, what the original purpose of the tune may have been. A tune originating as a secular folksong, or composed by Luther for a German hymn, by Purcell for a theatre song, by Handel for an oratorio aria, or by Haydn for a symphony movement, will appear in this index if (and only if) it was adapted for use with an English-language hymn and printed in that form in or before 1820; and it will appear only in its hymnic form.

Language, not geography, is the criterion. Consequently, various hymn tunes published in English-speaking countries, but only with Latin, Dutch, German, Italian, or Welsh texts, have been excluded. On the other hand, tunes published for use with English texts in France, Holland, India, Wales, and the Genevan Republic have been indexed.

Tunes

To match the strophic nature of hymns, a hymn tune should also be strophic. It is, of course, possible to set a strophic hymn to music without using a repeated tune. Through-composed hymns were sometimes titled 'anthems' or 'set pieces', but they were more often called simply 'hymns'. They are not regarded as 'tunes' for the purposes of this index.

Ideally, we might have wished to confine coverage to tunes designed for strophic repetition. But this criterion cannot be applied consistently in practice. When a tune is printed without a text, or with one stanza underlaid but without any additional text provided, there may be no way to know whether the compiler of this particular source intended or expected the tune to be sung to two or more stanzas.

Equally impractical is the other extreme, to include all settings of strophic hymns, whatever their form or length. A long set piece, such as Edward Harwood's enormously popular setting of Alexander Pope's The Dying Christian ('Vital spark of heavenly flame'), has sections in different keys and tempos and lacks any plan for strophic repetition. But it was sometimes called a hymn, and could still be regarded as a hymn tune by some stretching of the common understanding of that term. However, there is no logical way to draw a line between a set piece and a cantata. And if a cantata is accepted, why not an oratorio? Handel's Solomon is a setting of a sacred metrical text, but nobody would be tempted to call it a hymn tune.

Reluctantly, therefore, the editors had to use a rule of thumb to approximate the normal meaning of 'hymn tune'. We excluded any tune with either more than sixteen different lines of text, set as one stanza, or more than twenty-four musical phrases in one stanza. Any music going beyond either of these limits is treated as a set piece rather than a hymn tune, and has not been indexed. Anything within them has been included.

But some hymn settings repeat the same tune for several stanzas, then at the end add a brief amen, hallelujah, doxology, or other short coda, with part of the tune, or with entirely new music. We have included this kind of setting, even if its total length exceeds the limits given above; but what we have indexed is the strophic section-the 'tune'-with only a footnote reference to the coda. Occasionally there is a change of tune in the middle of a hymn. We have then indexed both tunes.

Many settings of hymn texts are soloistic in character: they sound more like arias or art songs than hymn tunes. Arias, duets, and even recitatives frequently have texts that do not differ from hymns in any essential respect. We had no wish to clutter our Index with music of this kind that nobody would think of calling a hymn tune. But we could not devise a strict definition that would exclude all 'songs' and 'choruses' while retaining all pieces that were conceived as hymn tunes. In the later eighteenth century many hymn tunes were highly ornate, even when designed for congregational use.

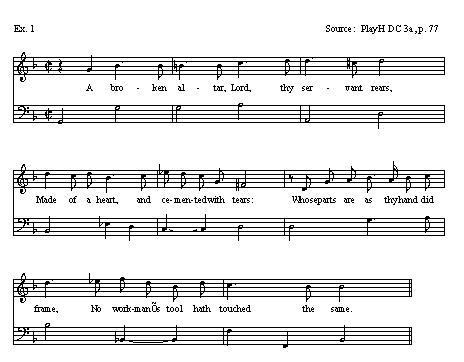

In this case we made context a determining factor. A setting with a topographical or other hymn-tune-like name, printed in a collection designated for use in worship, or in the company of other undoubted hymn tunes, will have been included; whereas the same music and text, printed in an oratorio or collection of sacred songs, may have been ruled out, or, quite possibly, will have escaped our attention altogether. (If we know of an earlier printing in a non-hymnic context, we refer to it in a footnote to the tune.) Several collections of hymn settings have been excluded in their entirety because the music was judged 'soloistic' (whether for one voice or more than one): that is, rich in melismas, leaps, ornaments, or pervasive imitation between voice and instrumental bass, even though each of these features is sometimes found in indubitable hymn tunes. Image Ex. 1 shows the beginning of a piece that was excluded as too soloistic to be called a hymn tune.

It should be emphasized that we have not excluded settings for solo voice and instrumental bass as such. If they are strophic, simple enough to suggest hymn tunes, and found in a context that gives some evidence of intended liturgical or devotional use, they have gone in. But each case was decided by individual judgement.

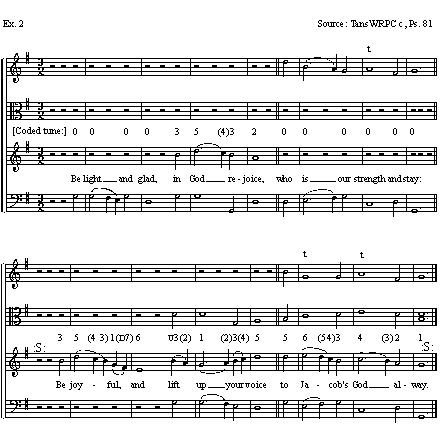

A further category of hymn setting that was excluded is the polyphonic motet, chorus, partsong, or canon. In this type of piece the voices are all treated equally, with imitative entries, varying rhythms and stress patterns, and generally free repetition of individual words and syllables; it is not possible to say that one voice is carrying a tune and the others are harmonizing that tune. Image Ex. 2 shows the beginning of a polyphonic motet that was not included, even though its text is the first verse of a metrical psalm in the standard Sternhold and Hopkins version. Canons and rounds, a popular feature of some eighteenth-century hymn collections, fall into this excluded category.

Contrapuntal texture of this description is also found in fuging tunes, a type of hymn tune that won great popularity in the later eighteenth century. But fuging tunes are clearly strophic, and moreover they always have some phrases in which one voice carries a simple tune, and only disintegrate into contrapuntal texture for some part of their length. The character of fuging tunes has been discussed elsewhere at considerable length. Although now more or less abandoned outside the American shape-note tradition, they were once a vital part of popular hymn singing. For these reasons, fuging tunes have been indexed, while wholly polyphonic pieces have not. Image Ex. 2 shows a fuging tune, indexed as tune 1729a.

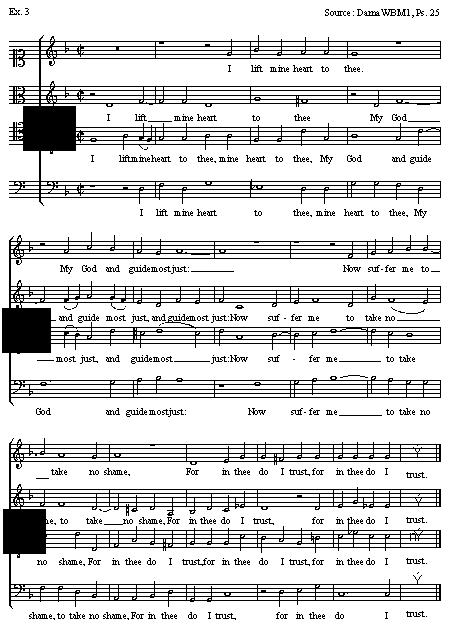

Another class of composition is the polyphonic setting of a plain tune, where the tune is treated as a cantus firmus in one voice while the others weave counterpoint around it. This was a feature of domestic hymn singing in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. It can be distinguished from a polyphonic setting of a sacred metrical text, such as Image Ex. 2, principally by the fact that one of the voices is singing a tune that is also known in monophonic or homophonic settings. Image Ex. 3 is a polyphonic setting of tune 269b, the tune being in the top voice. In some cases, the tune-carrying voice occasionally strays from the cantus firmus in an interpolation or, as here, in a coda, which is to be considered part of the polyphony rather than part of the tune. Such additions are mentioned in footnotes to the tunes in the Tune Census.

Sources printed

It was originally hoped to cover all musical sources, including manuscripts and organ barrels, but this proved impracticable. Manuscript sources of English-language hymn tunes have received little systematic study; some progress has been made, especially in North America. In addition to a large number of independent manuscripts, there are tens of thousands of copies of printed hymnals, and of bibles and prayer books as well, that are found to have tunes entered by hand on flyleaves, on added sheets, or even in the margins. The task of finding and indexing them all would be virtually endless.

It is possible to recover tunes from the barrels of a mechanical organ, even if the organ is no longer functioning. After some experimentation we concluded that the task was beyond our available time and resources.

At an early stage in the project, therefore, we decided to limit ourselves to printed sources. This has of course the practical advantage of a much higher degree of bibliographical control, including dating.

Printed sources were certainly a principal mode of dissemination of hymn tunes, especially new tunes, during most of our period. The exception is the period from about 1590 to 1680 (later in North America), when the repertory of tunes used in church was more or less fixed, and they were orally transmitted. Some tunes, of course, survive in manuscripts that are earlier in date than their first appearance in print, and in this sense the source we list as the earliest may not, in fact, be so. But it seems that the vast majority of surviving manuscript sources of hymn tunes from this period were copied from printed books.

Generally speaking, 'printed' means 'printed and published'. But a very small number of printed sources are not known to have been published (that is, offered for sale in substantially identical copies): sources like UC 3 (apparently printed for private use), or #SHT1-2 (given away by its compiler), as well as sources like TimbFDM a-r (in which every known copy is made up of a different selection of sheets, probably selected by the buyer). But they were printed, and so we have included them.

We have not indexed printed sources of texts that refer to tunes by name only. To be indexed, a tune must have been printed in some kind of musical notation, whether staff notation, lute tablature, alphabetic code, or staffless shape notes. Several sources have tune indexes with incipits printed in musical notation: these have not been separately indexed. One source (BartWBPM b) has some tune incipits in music notation instead of complete tunes: these, too, have not been indexed, but have been mentioned in footnotes to the tunes concerned.

1820

The time span of the Index runs from 1535 to 1820. The beginning date is determined by the earliest printed source of English hymn tunes in existence, Miles Coverdale's Goostly Psalmes. Robin Leaver has shown that this was published in 1535 or 1536. The ending date, 31 December 1820, is arbitrary. In the course of the nineteenth century, bibliographical control weakens: the number of published sources rapidly increases, while the number of reliable bibliographical studies diminishes. We had to concede on practical grounds that 1820 was as far as we could push our coverage in this project. We hope that others will eventually bring the cut-off closer to the present time, now that the method is established and the programming and database are in place.

A number of publications may date from just before or just after the final cut-off ('c.1820' or '1820-'). We have included them unless the balance of probability seems clearly to indicate that they were published after 1820.

Comprehensive

This word does not imply any claim to have found and indexed all printed sources, or even all extant printed sources, of English-language hymn tunes up to 1820. Such a claim would be ridiculous. It is our intention that is comprehensive. By every means we could find or devise, we have tried to identify, locate, date, and index all such sources. Nothing has been excluded because it was too difficult or too expensive to reach, although for some sources we have had to rely on other scholars for information, or to infer contents from our knowledge of other editions of the same work. But we have never 'indexed' books, or pages of books, that are not extant, however sure we may feel of the tunes they once contained.